Gene Editing in its “Prime”

Of the 25,000 genes in the human genome, it seems inevitable that there should be at least one person in your life where their DNA made some random mistake that screwed over the rest of their entire life. Nevertheless, with hope and perseverance, humans have carried on and worked hard for a way to combat these “natural” mutations. Subsequently, researchers have recently invented gene technologies that may provide exciting scientific breakthroughs in the biological field.

Let’s start with the basics.

Genes are units of heredity located in chromosomes that code for specific traits in an organism, meaning they are also responsible for the many disorders humans have accumulated throughout history i.e. sickle cell anemia and Tay Sachs disease. Chromosomes are made of DNA, carriers of genetic information, that is transcribed into RNA, which is then translated into proteins that determine our phenotype, which includes our appearance, our gender, but also genetic disorders.

Our DNA can be read as a long sequence of four bases (adenine, guanine, thymine, and cytosine), and this sequence is responsible for our entire biological identity. Take sickle cell anemia for example. Amidst the long sequence of nucleotide bases, a single base substitution (there is a thymine where there is supposed to be an adenine) causes red blood cells in an individual to take on a shape of a sickle, which are distorted and cause a number of health issues.

Genetic engineering, in theory, allows us to modify DNA in vivo (in the cell of an organism), allowing us to repair mutations back to their supposed sequences and cure genetic disorders in seemingly inconceivable ways. The newest proposed method, known as prime editing, is said to be the most efficient way to edit genes, and its inventor, David Liu, claims that it has the potential to cure up to 89% of genetic disorders. Though professed as effective by Dr. Liu and his laboratory partners, this method is so relatively new that it is still undergoing extensive research, and has thus been called for a moratorium. But since prime editing is fairly complicated, it would be best to first explain how a prior genetic engineering method, CRISPR, works, as to obtain a better understanding of prime editing.

Thank you, bacteria

CRISPR-Cas9 stands for “clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats,” using the enzyme Cas9 as its primary tool in genetic modification. Interestingly enough, this method was discovered after researching the adaptive immune systems of bacteria, and we exploited this defense mechanism into our own gene editing tool.

When viruses infect a cell (in this case, a bacterium cell), they inject their DNA, which is then integrated into the nucleus of the infected cell until the virus is in complete control. However, the CRISPR system in a bacterium allows it to take out a portion of the viral DNA, known as the protospacer, which is then reinserted into its chromosomes as a part of a CRISPR array. (The cell can differentiate between its own protospacers and the viral DNA sequence because the viral DNA sequence is always followed by a specific protospacer adjacent motif sequence, known as PAM.) In this stage known as spacer acquisition, a Cas1-Cas2 protein complex, allows cells to record the viruses that bacteria have been exposed to into its CRISPR array as a spacer sequence. Furthermore, this spacer sequence is also passed on to the cell’s progeny to protect future generations from past viruses. Afterwards, transcription of the array gives the CRISPR complex a single guide RNA that can be used to detect the foreign DNA should it reappear. Upon recognition of the same viral DNA or PAM sequence, the guide RNA binds to a Cas-9 protein, which acts as a type of molecular scissors that creates a double-stranded break in the viral DNA. The guide RNA is composed of two sequences, a spacer and a scaffold, where the spacer is responsible for locating the mutated sequence and the scaffold is the complementary RNA sequence that allows the protein complex to bind to the DNA of the target sequence. This is followed by, of course, the cutting of the intended position by the Cas-9 protein.

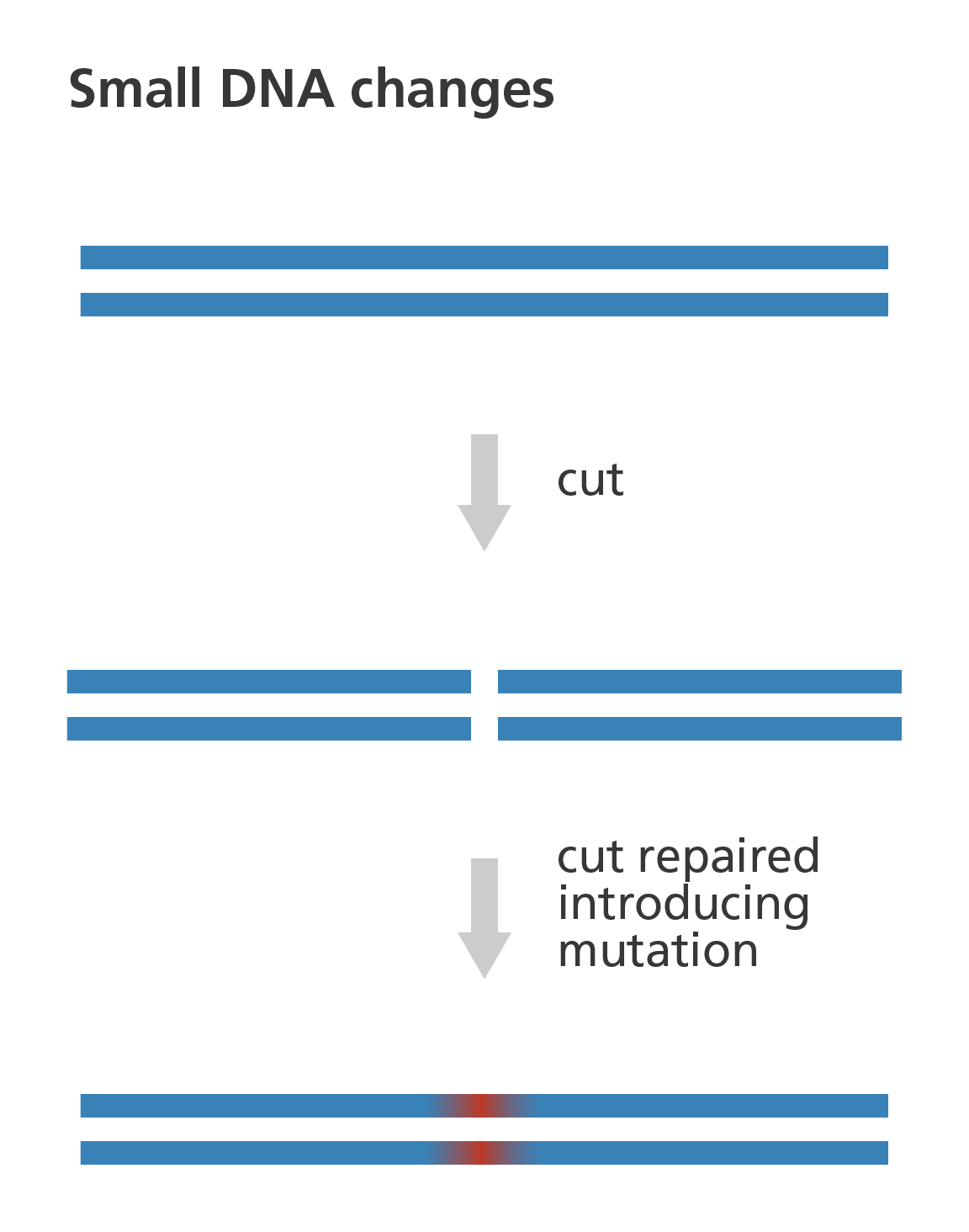

Scientists have found a way to program this CRISPR-Cas9 complex to recognize particular DNA sequences and make a break at such sites. The disruption in this DNA is then followed by either one of two repair pathways: non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR). NHEJ is the provocation of cells to “repair” the breaks caused by the Cas-9 endonuclease, and is usually the immediate effect after the DNA is cut. However, if a donor DNA template is included with the CRISPR-Cas9 complex, then HDR is enacted, and new genetic information, in the form of the DNA template, may be incorporated.

But… CRISPR-Cas9 can be impractical in curing human diseases due to multiple ethical considerations and challenges with delivery, especially in regards to the off-target effects that may also occur that alter the DNA at unintended sites as well. This is because the CRISPR method brings about a break in both strands of the double helix structure at the target location of the DNA sequence, which causes the cell’s natural repair apparatus to hastily fix the damage such that it usually leads to erroneous insertions or deletions. Many studies have shown that double stranded breaks are known to cause DNA translocations, cell senescence, or tumor genesis, which obviously, we definitely do not want.

Now for the scientific breakthrough

Invented by the Liu Group in 2019, the prime editing technique is “a new approach of genome editing in which a reverse transcriptase directly copied edited DNA sequences into a specified target site from an extended guide RNA without requiring double-stranded breaks or donor DNA templates.” The easiest way to comprehend this is to think of this as a search-and-replace method of editing genomes, where the protein complex navigates through the cell to find the mutated or viral DNA and nicks one strand of the DNA. After the endonuclease Cas-9 cuts it, it is then replaced with the programmed “correct” DNA. I know it sounds a lot like CRISPR, but I will explain in detail the differences between these gene editing techniques. For now, one can treat this technique as a “superior” method, since it makes more subtle, precise incisions with a much smaller chance for failure due to its single-stranded breaks that avoid “genome vandalism.”

Why is this of any importance? Prime editing is a significant step in the field of genomics because being able to make any kind of DNA change at any site in the human genome is now an aspiring reality, rather than just science fiction. Unlike preliminary CRISPR technology, prime editing has been proven to be able to successfully fix the mutations involved in sickle-cell anemia and Tay-Sachs disease in cell cultures. Of course, prime editing has its limitations, as it has been tested rarely in vivo and still requires many more reproducibility experiments since it is still in its early stages, but the exciting notion is that the technique is being optimized by researchers at this moment. The reason many people are optimistic towards this approach is because prime editing appears to be the key to curing many genetic diseases, holding amazing potential in its efficiency and wide range of possibilities.

From CRISPR to prime editing

So how does prime editing actually work? This method was derived from the CRISPR system in bacteria after Liu and his partners realized that the biggest problem with CRISPR was its double-stranded breaks. Thus, this remarkable improvement upon CRISPR uses components from the CRISPR-Cas9 method and places its importance on its own prime editing complex, a Cas-9 enzyme fused with a reverse transcriptase and a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA).

In this case, the Cas-9 enzyme has been engineered in a laboratory setting to cut only one strand of the DNA, and the pegRNA has two components: a binding region and an edited region. The binding region of the pegRNA is a complementary sequence to the target sequence, allowing it to quickly locate and bind to the mutated DNA. The edited region of the pegRNA is a complementary sequence to the “correct” or intended DNA sequence, and it is used along with the reverse transcriptase to create the intended strand of nucleotides. Since the pegRNA has a region that codes for the correct DNA sequence, a donor DNA template is not needed.

So, prime editing begins when the pegRNA finds and binds to the target sequence; this is followed by the Cas-9 protein, and its active site binds to and cuts the DNA strand. The reverse transcriptase that is fused with the Cas-9 protein then reads the RNA sequence on the edited region of the pegRNA and reverse transcribes it to the corresponding nucleotides that are in the intended sequence. This correct sequence is now appended to the DNA where it had originally been nicked.

However, a new problem arises. Because DNA is double-stranded with both strands complementary to each other, the new DNA sequence creates a mismatch in the target site with one edited stranded and one unedited (mutated) strand. Naturally, mismatches are fixed by the cell’s automatic repair system, but the cell’s repair apparatus does not know which strand to repair.

It is now that the Cas-9 protein is guided by the pegRNA to make a small nick on the unedited strand, which prompts the cell into thinking that the unedited strand is the one that is wrong. (If a strand is cut, it probably means that there is a problem with it.) Finally, the cell will innately use the edited strand as a template to code for the intended edited complementary sequence, and prime editing is now complete!

I know that was quite a lot of information to take in, so I hope this chart can break down and highlight the differences between prime editing and CRISPR.

Understanding the hype!

What does all this hold for the future? One by one, scientists and health experts hope to be able to use this prime editing technique to fix disorders caused by mutations that CRISPR can not, such as mutations in the nervous and cardiovascular system. Its versatility and precision also allows for the exact DNA changes that some disorders like progeria and muscular dystrophy call for. With this novel innovation, we now have greater flexibility in basic research and therapeutic applications; buzz is generating throughout the scientific community as well.

Beyond treating diseases, however, the innovation of prime editing plays an essential role in scientific research and biotechnology. It is giving us extensive insight on the biology of many diseases and disorders as well as more understanding in the evolutionary defensive adaptations of a variety of organisms. Prime editing also has a crucial aspect to understanding the role of bases in cancer-related genes. And with respect to biotechnology, prime editing has allowed us to modify crops that are more resistant to disease, pesticides, and drought. Ethical considerations must also be put into place when discussing prime editing, as it may be used in the future for genetic enhancement, perhaps in the future, allowing humans to choose desirable traits for their offspring.

But with all the current excitement towards prime editing, we must also consider its flaws. One of the reasons this method has not reached clinical trials is the multitude of limiting factors that also come into play including, but not limited to, chromosomal location, local sequence context, potential off-targets, the type of cell, and developmental stage of the cell. This means that the idea of curing 89% of genetic disorders correlated with mutations is only an idealistic possibility, with everything occurring in the favor of the scientists. There is also a chance that the reverse transcriptase could continue transcribing past the edited region of the pegRNA, causing an extra incorrect sequence to be inserted into the genome as well. And lastly, since this technique has only been used in vitro, the delivery or integration of this method into the immune system would certainly be difficult.

For the moment, prime editing is a baseline that underscores the intense amount of progress that is being made in the genomics community.

References

https://liugroup.us/research-overview/genome-editing/

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-019-1711-4

https://www.synthego.com/guide/crispr-methods/prime-editing

https://www.nibib.nih.gov/news-events/newsroom/scientists-unveil-search-and-replace-genome-editing

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ydb8ejtDoZw&t=72s

https://hippocratesmedreview.org/prime-editing-one-step-closer-to-perfect-gene-editing/

https://twitter.com/circuit_logic/status/1186644783751544832

https://innovativegenomics.org/blog/cas9flap/

Additional Resources